“Why did you say five minutes?”

Whovians have only had one season away from the Eleventh Doctor, and it’s rough for some to remember that this year isn’t a brief reprieve before his return. Fans are missing his childlike wonder, his comforting cadence, his attractive-science-professor fashion sense, his undeniable sweetness in the face of a universe worth of terrors.

Is that his legacy, though? Safe to say that he will be thought of fondly, but that’s not what made his run remarkable.

When the Eleventh Doctor appeared on The Sarah Jane Adventures, he met up with two former companions—the show’s eponymous leading lady and Jo, who’d been the Third Doctor’s pal during his Earth-bound UNIT days. After realizing that Sarah Jane had seen the Doctor even following her time traveling in the TARDIS, Jo assumes that the Doctor hadn’t liked her very much; why had he never visited? The Doctor admits to her that he did, that he had observed from a distance. That before the Tenth Doctor regenerated, he went to visit all of his former companions, to peek in on their lives and find out how they were doing.

And what he found was remarkable. All these people whose lives he had touched—they had all managed to live extraordinary lives of their own. They were having grand adventures, helping others, using everything they had learned to better the world. None of them had stopped just because he’d left them behind. They were every bit as remarkable as the day he’d met them, and then some.

This was a theme throughout Russell T. Davies’ tenure on the show—that knowing the Doctor encouraged ordinary people to do incredible things. That traveling with the Doctor meant that you would never be satisfied with a humdrum day-to-day existence. You’d seen the universe, you’d traveled through time, and you were obliged to be amazing. It was an uplifting message for sure, and it was meant to reflect outward to the audience; you’ve witnessed these adventures too, now you go and be amazing. A beautiful sentiment for a show that is aimed at children, dreamers, and would-be heroes.

Then Matt Smith showed up, and he seemed to play into those exact sensibilities, perhaps even moreso. A watchful guardian of crying children, a mad man with a box, one of the most encouraging and praising versions of the Doctor yet.

So it’s interesting—isn’t it?—that the Eleventh Doctor’s run is primarily marked by loss and failure. His track record is perhaps only comparable to the Fifth Doctor (Peter Davison) in how many unwanted goodbyes he had to make, what he sacrificed, and how often he lost the larger battles. This isn’t to say that the Eleventh Doctor’s achievements (of which there were many) are somehow unremarkable. It’s simply that the Eleventh Doctor’s failures are what set him apart, what make him distinct in the show’s current run, when he uprooted Who’s newer set of mythology in favor of a centered, family-like dynamic.

That family, of course, is the Ponds. The Doctor has had family with him before, in a very real sense—he began these adventures with granddaughter Susan—and he has enjoyed certain adopted families on pit stops (the Tylers being the most obvious among their number), but the Ponds were not the same. They came in and out of his life year by year. They ran away with him on their wedding night, and set a place for him at Christmas dinner, every Christmas. They let him live in their house for a while. And certainly, they owe some of their successes to him; he encouraged them to look beyond a future in the sleepy town of Ledford.

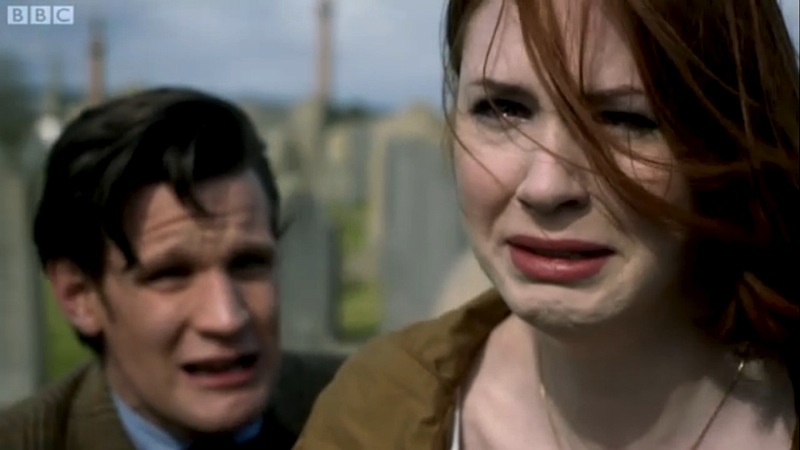

But it all came to an abrupt ending in New York City. We can say that Amy and Rory were still happy after being stranded in the past, that they never blamed the Doctor for their lot or held it against him. That doesn’t change the fact that their fate was not part of the plan. That the Doctor had a very hard time keeping the promises he made to them, and a harder time telling them the truth when they needed to hear it. That—if we want to take the long view of Amy’s life—the Doctor damaged her as a person in ways that are unimaginable to your average human being. It seems like a fairy tale, but it’s not the “happily ever after” sort. It’s the one where the fairy godmother gets all your wishes wrong, and you’re left with a great big mess to clean up on your own.

Think about it: Amy spends the majority of her childhood being told that the man who rescued her from the monsters in her house is made up. She is sent to countless child psychologists who tell her she’s clinging to a fantasy. She’s encouraged to call this man her “imaginary friend.” Her fantasies cause her to be teased mercilessly. She changes her first name to distance herself from the girl who believed in that raggedy phantom, but the only people who she truly allows close are willing indulge that fixation; Mel asks her questions about the Doctor all the time, and Rory is willing to pretend to be him.

Amy might have come out of this less scathed, but for one tiny problem: Her encounter with the Doctor was real and she knows it. Having your real experiences passed off by droves of adults because you can’t prove them is bound to make you distrusting. But she’s lucky! Her imaginary friend returns to her, and he didn’t mean to be late, it’s just that time travel is sort of like building a house of cards backwards, and he can’t really be held to these things. Right?

It is remarkable because the Doctor never screwed up a meet cute so badly. Martha’s stop outside the hospital was out of joint, but didn’t mess too badly with the fabric of space-time, Donna refound the Doctor after a relatively short period of searching, even Sarah Jane Smith (who felt somewhat betrayed over being abandoned by the Fourth Doctor) didn’t rack up the early development nightmare that was Amy Pond’s childhood. Making that mistake, it could be argued that the Doctor felt the need to make it up to her in the grandest of fashions… but that doesn’t go at all as he planned.

The Doctor gamely attempts to fix things by making life easy for the Ponds. He situates Amy and Rory in such a way that they flourish back on Earth—nice home, fancy car, perfect location for Amy to start a modeling career. Interestingly, the Ponds have no desire to pursue great deeds outside of their time with the Doctor. They’re not like the Sarah Jane Smiths and Jo Grants and Tegan Jovankas and Ian and Barbara Chestertons that traveled with the Doctor before—rather than working toward improving and safeguarding the world around them, Rory and Amy are busy trying to keep their own lives together. And it takes them quite a long time to find that equilibrium; the Doctor has to intervene again to save their marriage, when it falls apart after Amy finds she can no longer have children. Yet the Doctor takes it upon himself to fix their marriage—and he succeeds.

It’s no wonder that one of the primary themes of Amy’s tenure on the TARDIS is her need to let go of the Doctor. And despite her revelation in “The God Complex,” a moment when he Doctor himself tells Amy that she needs to grow beyond him, she still requires his help to salvage her life. You can’t really blame her in this—she’s used to the Doctor showing up to fix her problems. But because little Amelia holds the Doctor up as a hero for so long, she never takes him to task for the difficulties he alone inflicted on her life. She loves him too much. She believes in him no matter how many times he lets her down. Which may go far in explaining why, when her infant daughter was stolen from her (an act directly caused by her association with the Doctor), she trusted the Time Lord to get the baby back—which he never manages. Instead, the Doctor offers several bland excuses, then conveniently never bothers to come clean and admit that he can’t do it. He cannot restore Melody Pond (now River Song) to her parents. She will grow up trained to murder him, then to love him, and then wind up in prison for a good long while. Occasionally, he’ll drop her off for a glass of wine with dear old mum. Same difference?

Poor River Song. The Doctor never really does well by her either. Never finds her in childhood, never rescues her from Madame Kovarian’s conditioning, never puts the proper effort forth in helping her to reconnect with her family as an adult. (And yes, she spends childhood time with them as Mel, but that barely counts, since her whole purpose then is using her future-parents to find the Doctor.) In fact, River spends all of her time rescuing him—from a foretold death by messing with time, from an unforetold death by giving him all of her regenerative energy, from having to say the words that will lead Amy to follow Rory back in time and live out the remainder of her life in the past. She also spends most of her time absolving the Doctor of responsibility with catch phrases: “The Doctor lies.” “He doesn’t like goodbyes.” What River is constantly masking on the Doctor’s behalf are his shortcomings, his errors. She’s maintaining his legend, even at moments when he’s not up to snuff.

Then the Ponds are gone from his life, and we arrive at Clara Oswald. The “impossible” companion whose whole purpose hinges on fixing things for the Doctor. She kicks him back into gear when she finds him in “The Snowmen,” and then proceeds to get him back to his old tricks when he encounters her in present day. When the Doctor heads to Trenzalore to confront his supposed grave, we find out that Clara has a special function as a companion. With the Great Intelligence threatening to wipe out his existence, Clara throws herself back through time and space, showing up during key points in the Doctor’s life to shove him back in the right direction. It turns out to be the whole reason she is traveling with him at all. He requires Clara—and the telepathic ghost of River Song—to defend him from a universe that worries he has grown too powerful, too grand, too dangerous to continue.

And when the Doctor chooses to live out the remainder of his life in a town called Christmas, he does so while simultaneously defending its inhabitants and watching the entire run of its occupants’ lives. He’s probably come to expect it by that point. The Eleventh Doctor has lost so many people; the child that was Amelia Pond, Rory over and over, Clara over and over, Brigadier Lethbridge Stewart—not just the random ones who get caught in the crossfire, but people who are vibrant and close to him. How could an entire town, generation by generation, be all that surprising? Yet again, it’s Clara who pulls him out of the fire, asking the Time Lords to give him the top-up he needs to destroy the Daleks and regenerate.

Is it any wonder that the next Doctor needed to ask Clara whether or not he was a “good man”? Even on his best days, the Eleventh Doctor must have feared that answer. He lost a family, a lover, old friends and new ones, and it’s likely that he didn’t feel that same swell of pride the Tenth Doctor garnered from looking in on his old companions. Eleven had to have wondered whether or not he was a benefit to the lives he touched—and their weren’t many who were in the plain affirmative on that question. (Craig? Kazaran?)

But despite how morbid that seems, this was everything that made the Eleventh Doctor unique. When you look back on the show’s tenure, his specific inability to create magical fixes, to better the lives of the people who mattered most to him, that is what makes Eleven’s story so potent. He danced around those problems, or wove through them the wrong way. He lied. And it made him into a fascinating incarnation of a character five decades in the making. Which is just as—or more—important than being lovable any day of the week.

Emmet Asher-Perrin has a lot of feelings about how much the Doctor screwed up poor Amy Pond. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr. Read more of her work here and elsewhere.